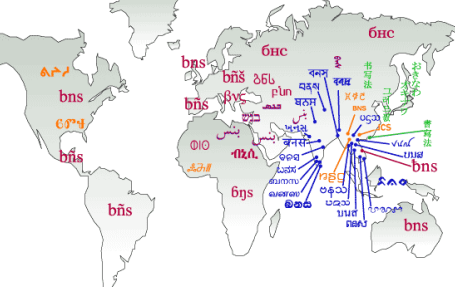

In first world countries, there seems to be a divide between who is educating and who is learning. According to Bradbury (2020) there is a significant attainment gap in the way students are marked when it comes to Primary school and their baseline assessment policy, specifically for students with English as an Additional Language (EAL). Within that category, I have realised there are some students who understand the Latin alphabet giving them an advantage at baseline assessment. However, it could be argued that countries using script other than Latin, such as Cyrillic, Ge’ez, Hindi, Chinese etc, the baseline assessment results could skew towards the lower end for these children. Potentially discriminating against children with EAL- reinforcing notions of Western superiority.

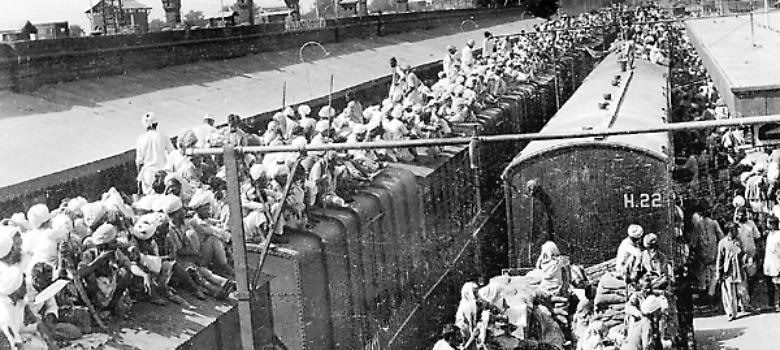

Although baseline assessment was scrapped in 2016, a new version has been reintroduced in 2020. This could be due to an increase in children who speak EAL, and there are 2 reasons for it. One being that people come to first world countries as refugees, and the second being economic migrants. According to Achiume (2019) economic migrant’s are normally viewed suspiciously by Westerners who are afraid of them taking their resources, because the economic migrant aims to seek a better situation for themselves and their family. Often starting from the bottom rungs of society and working their way up. Achiume (2019) calls this act ‘Migration as Decolonisation’.

The rethinking of migration as decolonisation has significant policy implications. It suggests that First World countries have a moral and political obligation to open their borders to migrants from former colonies, acknowledging and rectifying past and present injustices. Part of this rectification should also include educational policy and the effects on children learning the language to start with, and what prejudice learners might be faced with. Bradbury (2020) integrates policy sociology and Critical Race Theory (CRT) to create a framework for analysing education policy.

Policy sociology studies the development, implementation, and effects of policies within social contexts, focusing on power dynamics, social structures, and cultural influences. It examines policies as discourse and practice rather than a rule, considering how they shape identities, distribute resources, and construct social realities, emphasising context and the role of various actors (Ball, 1994).

CRT, according to Delgado and Stefancic (2017), examines how racism is embedded in societal and legal systems, emphasising systemic racial inequalities. It advocates for recognising and addressing these issues by including marginalised perspectives.

This framework initially explores the relationship between policy and racial inequalities, it then tackles ‘Policy Bias’ as an implication of exclusion to avoid perpetuating white dominance while appearing neutral and/or meritocratic. This frame work could improve the career trajectories of marginalised people of colour, especially in institutional environments such as education.

Garrett (2024) argues that institutional environments perpetuate meritocratic ideals that exclude working-class and racialised students. This leads to precarious career paths, therefore structural issues in higher education must be improved through diversity and inclusion efforts. However there seems to be a fear of impeding freedom of speech at universities for academics according to the series of vox pops conducted by Orr (2022). To counteract this, I argue that change is frightening, but necessary to create an equitable environment- but this can only be achievable with open enquiry.

(Word count: 539)

Resources

Ball, S.J. (1994) Education Reform: A Critical and Post-Structural Approach. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Ball, S.J. (2006) Education Policy and Social Class: The Selected Works of Stephen J. Ball. London: Routledge.

Bradbury, A., 2020. A critical race theory framework for education policy analysis: The case of bilingual learners and assessment policy in England. Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(2), pp.241-260.

Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. (2017) Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. 3rd ed. New York: New York University Press.

Garrett, R. (2024). Racism shapes careers: career trajectories and imagined futures of racialised minority PhDs in UK higher education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, pp.1–15.

Orr, J. (2022) Revealed: The charity turning UK universities woke. The Telegraph [Online]. Youtube. 5 August. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRM6vOPTjuU

Achiume, T. (2019) ‘Migration as Decolonization’, Stanford Law Review, 71(6), pp. 1509-1574. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3330353 (Accessed: 16 June 2024).

6 responses to “Inclusive Practice: Blog 3-Education and Race”

Your blog post is very eye opening with its very concentrated focus on the attainment gap of EAL students. Your introduction makes the stakes of this argument very clear: the potential for systemic bias against EAL students which reinforces notions of Western superiority.

You follow up this thesis with very strong support from an array of academic sources. I found this position very convincing. I appreciate your final conclusion that “change is frightening, but necessary”.

As a reflect on how to bring the insights from the IP course into my own practice, I wonder what changes might be most frightening and what motivates those fears. I question how those obstacles can be overcome and the potential upside to facing those fears head-on. Overall I agree that an environment that welcomes “open enquiry” is necessary to achieve those goals.

Thank you Adam, You perfectly captured the essence of the blog post’s focus on the attainment gap for EAL students. I’m grateful to hear that my points on systemic bias and its reinforcement of Western superiority struck a chord with you, and I appreciate that you consider my blog well academically supported It’s great to know that the argument felt convincing and well-supported.

You raise a particularly important point with regards to students who understand the Latin alphabet over those who use script ‘Cyrillic, Ge’ez, Hindi, Chinese’. It highlights the difficulties of monolingual approaches in primary schools, particularly when bilingualism is denied which can be detrimental to children’s learning experiences and well-being. Additionally, how globally dominant the English language over other languages, which again can have detrimental effects such as loss of other languages, not all students having access to be able to learn English. I also agree that change is necessary as you rightly point out to ‘create an equitable environment’ something that bell hooks talks about in her chapter ‘Embracing Change’ where ‘making the classroom a democratic setting where everyone feels a responsibility to contribute is a central goal of transformative pedagogy’ (hooks, 1994).

Thank you for sharing the term Monolingual with me Sheran. The global dominance of the English language is another crucial point you raised. It often leads to the loss of other languages and can disadvantage students who don’t have the opportunity to learn English. Addressing this imbalance is key to ensuring all students have equal access to education.

I’m totally with you on the need for change to create an equitable environment. Bell Hooks’s concept of making the classroom a democratic setting where everyone feels responsible for contributing is so inspiring.

Hi Leila,

I learnt a lot through your blogpost, the connection you establish between countries using script other than Latin skewing the results to the lower end for children not familiar with the latin alphabet, reminded me briefly about my experiences learning English in school. My teachers were confused why I would pause between every word not forming proper sentences whenever I spoke to them. It was later revealed that my Mum was the person teaching me to speak English at home in the way that she was taught to speak Thai, where the Thai language sort of pauses between every word. English was not my additional language but it was for my Mum, so perhaps there are even more nuances in play here for the children who have EAL as they will only be able to practise at home where English may or may not be spoken which again puts them at an unfair disadvantage.

You mention what Achiume terms ‘Migration as Decolonisation’ and that first world countries have to rectify past and present injustices which include educational policy.

I was thinking about what this might mean in my own context in Design education, as Danah Abdulla mentions design is a political act every decision designers take can exclude or oppress, that colonial power structures formed in society dominate our understanding of design (https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/).

The IP unit has shown us that we need to dissect, and reinvent our knowledge structures to change, and as you mention change is frightening but necessary.

Thank you for sharing your personal Experience Jon, I’m really grateful that you shared your story about language learning. Your experience learning English is a perfect example of how language nuances can create challenges. It’s fascinating how your mum’s teaching influenced your speech patterns, and you’re absolutely correct about the nuance in learning new languages- you’ve made me think about how interaction shapes our language habits. Kids who learn English as an additional language (EAL) often face similar issues, especially if English isn’t spoken at home. This can definitely put them at a disadvantage, much like how non-Latin scripts can skew learning results.

In the context of Design education, reshaping policy for Justice becomes even more critical. Danah Abdulla’s point about design being a political act is so true. Thank you for sharing this with me.